CIDRAL PGR Poster Competition

In 2024-2025 CIDRAL held its third PGR poster competition. Any doctoral student registered in SALC was eligible to enter a poster that showcased an aspect of their research.

The following were chosen as the winning entries:

First Prize: Ruoyi Zheng

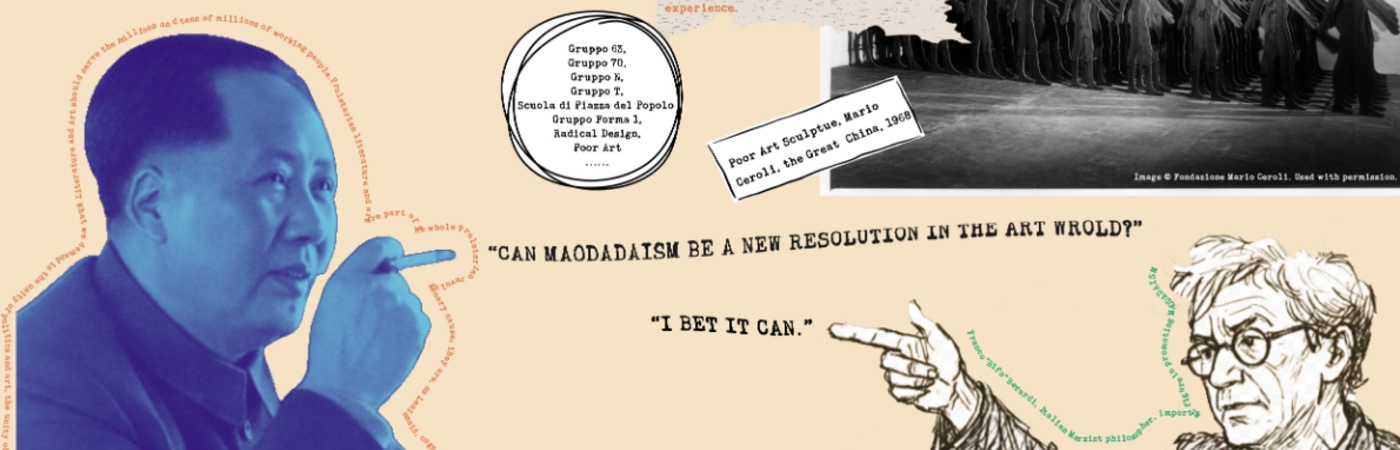

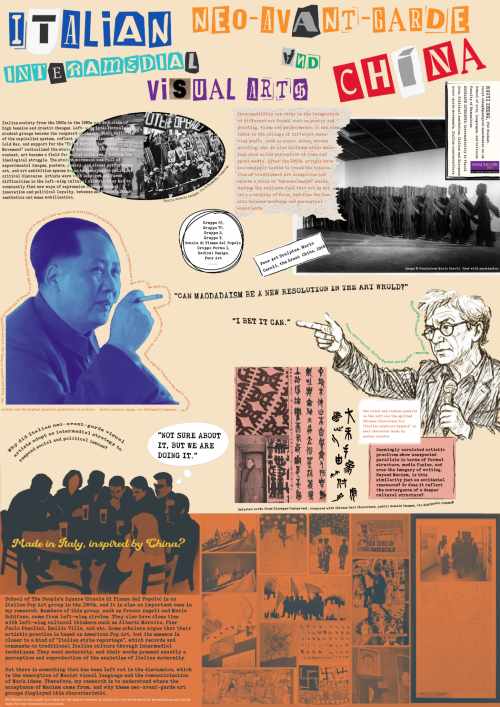

Can Italian neo-avant-garde intermedial visual arts and China relate to each other?

Having Western Europe's largest communist party in the second half of the 20th century, Italy presents a particularly compelling case study for my research which examines why and how neo-avant-garde movements of the 1960s-1980s engaged with Chinese cultural-political aesthetics. Traditional scholarship has typically viewed avant-garde movements as internal institutional challenges, focused primarily on debates around art’s autonomy and heteronomy within Western contexts. However, few scholars have recognised how globalisation and internationalisation transformed these movements into cross-continental exchanges that surpassed single national revolutionary frameworks.

It is obvious that art became a field for ideological struggle between left-wing politics and traditional institutions as artists responded directly to Cold War geopolitics and the contradictions of the capitalist system. In this period, artistic innovation sometimes was inseparable from political loyalty, with experimentation continuously finding new ways of expression between innovation and societal critique. Among which, intermediality, the integration of different mediums emerged as a powerful tool for depicting art and reflecting ideology. In Italy, different art groups developed distinctive intermedial practices. These artists deliberately blurred traditional media boundaries through collage, photomontage, and the integration of text with visual elements. All these approaches presented a unique perception and reproduction of Italian modernity, often incorporating political discourses (including Maoist imagery) into compositions.

However, it would be reductive to view this engagement with Chinese aesthetics as purely political. Delegations of Italian artists and intellectuals who visited China returned with impressions of a mysterious and sophisticated East that transcended political ideology. The formal resemblance between certain Italian abstract experiments and Chinese calligraphic traditions raises questions about cross-cultural aesthetics, perhaps human aesthetic sensibilities follow universal patterns despite cultural differences, or perhaps they constructed China as an exotic “Other” that provided aesthetic escape from Western difficulties?

In addition, the poster’s design deliberately mimics the Italian neo-avant-garde aesthetic by adopting collaged elements, fragmented texts, quotations, and more. The layout intentionally rejects traditional organisation of information, embracing instead the radical visual strategies employed by publications like A/traverso, which was established by self-proclaimed “Mao-Dadaists” in the 1970s. This design approach is not merely decorative but methodological. The deliberate absence of prescribed reading order, the fragmented and non-linear arrangement of information, allow viewers to begin wherever their attention is drawn. I seek to convey not just information about my research but to embody their methodologies, allowing viewers to re-experience the art experiments in the 20th century.

Second prize: Laila Zulkaphil

The need for humanitarian aid globally is higher than ever before. According to the United Nations, 122 million people are forcibly displaced, and 305 million people need urgent humanitarian assistance as a result of intensifying conflicts, increasing climate-related disasters, and staggering food security crisis. Only half of the global humanitarian funding requirement of $49 billion was covered in 2024. Recent aid cuts by major donors have exacerbated this already significant funding gap and sent the entire humanitarian system into crisis. Immediately upon taking office for the second term, President Trump initiated an abrupt and chaotic dismantling of the US Agency for International Development, the largest donor accounting for 40% of global humanitarian aid contributions. Other donors such as the UK, France, and Germany have also announced aid cuts to boost defense spending. Amid this funding crisis, humanitarian actors are turning to innovative financing mechanisms, particularly ones that promise to mobilize private sector resources. One such mechanism is social impact bonds (SIB), where private investors fund projects upfront, repaid by outcome funders if projects succeed.

My research critically examines the use of SIBs in humanitarian response through two case studies: the Humanitarian Impact Bond implemented by the International Committee of the Red Cross in Mali, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Refugee Impact Bond implemented by the Near East Foundation in Jordan. Findings reveal that SIBs do not mobilize additional humanitarian funds as traditional donors still pay. Although SIBs offer outcome-focused flexibility and opportunity to innovate – advantages over rigid traditional funding – this potential is underutilized in practice. While SIBs may hold niche value in high-risk experimental programs, their current application risks diverting scarce resources to private investors and to cover significant administrative costs without bringing unique benefits for aid recipients. As the first in-depth academic inquiry into the humanitarian application of SIBs, this study underscores the importance of ethical evaluations to ensure financing tools prioritize aid effectiveness over market interests. Using an interdisciplinary approach based on market ethics, humanitarian principles, and different schools of thought in moral philosophy, my research investigates if the use of SIBs in a humanitarian context is ethical.

Third prize: Dyuti Gupta

Complexities of Care: Studying Nurse Narratives of the First World War

My doctoral thesis offers a decolonial intervention in First World War medical care scholarship by placing interdisciplinarity at its core. Drawing together the fields of First World War studies, medical humanities, social history, gender studies, and literary theory, the project develops a method for reading care narratives of the war through the lens of race, gender, class and nationality. It examines both publicly available texts and archival materials, bringing to light previously little-known documents that trace the composition of published works, and proposes a new way of understanding encounters with the ‘other’ in the context of wartime caregiving.

The first two chapters analyse the writings of Kate Luard, Vera Brittain, and Ellen La Motte—nurses who served during the Great War and described what it meant to care for ‘foreign bodies,’ including Indian sepoys, French soldiers, and German prisoners of war. The final chapter takes a retrospective view, focusing on oral histories and analysing nurses’ memories of encounters with non-white soldiers, recorded in the 1970s and 1980s and held at the Imperial War Museum.

Combining textual analysis with archival research, my work offers a new approach to the historiography of wartime nursing—one that foregrounds the mental and political ambivalence of carers in their encounters with national and racial otherness. Looking at narrative perspective, retrospective narration, and expressions of doubt, as well as cultural and political sensibilities, the thesis develops a theoretical framework drawing from modernist studies, care studies, social history, and decolonial theory. Divided into three chapters, my thesis explores how the presence of the wounded foreign and nonwhite bodies shape the nurses’ subjectivity and responses; how the politics of painkilling drugs such as morphine interacted with concerns of gender, class, race, and colonialism (especially the opium trade) to shape wartime care practices; and how the standards of hygiene practiced by nurses, often situated at the intersections of medical and colonial discourses, affected their self-perception as caregivers and their impressions of the patients’ behaviour and needs.